For our fifth article about the problems with the Yale Integrity Project, we share Part 3/3 of the critique by Jesse Singal. Republished here in full with the permission of the author.

Jesse Singal brings us up to date on significant events and publications since he published his second piece in this series. Then he dives into a deep and detailed analysis of the misunderstandings and mis-statements in the Yale “Integrity” Project’s white paper.

Originally published on Jesse Singal’s substack, Singal-Minded here: https://open.substack.com/pub/jessesingal/p/yales-integrity-project-is-spreading-ba7?r=427k8t&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Yale’s “Integrity Project” Is Spreading Misinformation About The Cass Review And Youth Gender Medicine: Part 3

This was all really, really bad

Jan 01, 2025

In August and September I published a two–part response to a white paper titled “An Evidence-Based Critique of ‘The Cass Review’ on Gender-affirming Care for Adolescent Gender Dysphoria.” That paper, published by Yale Law School’s Integrity Project (and promoted by the law school itself), was co-authored by Meredithe McNamara, Kellan Baker, Kara Connelly, Aron Janssen, Johanna Olson-Kennedy, Ken C. Pang, Ayden Scheim, Jack Turban, and Anne Alstott.

As I pointed out, McNamara et al. (as I’ll call it) was riddled with errors, misunderstandings, and distortions. But despite the length of those first two posts, there was a lot I didn’t get to, and I realized that if I wanted to cover what I wanted to cover, there would need to be a Part 3.

I’m extremely overdue to this. Since I published Part 2, Olson-Kennedy, one of the co-authors of this supposed debunking of the Cass Review, admitted to The New York Times’ Azeen Ghorayshi that she and her team are, due to the heated politics of this issue, sitting on apparently less-than-promising data about puberty blockers rather than publishing it. In addition, as I reported in The Economist, Olson-Kennedy was recently sued by a former patient who has detransitioned and who claims that she was quickly pushed toward physical interventions she now regrets (Olson-Kennedy’s own notes support this former patient’s account).

Most importantly for our purposes, a peer-reviewed response to McNamara et al. was recently published in Archives of Disease in Childhood, the journal that published the Cass Review’s systematic reviews. That paper was co-authored by C. Ronny Cheung, Evgenia Abbruzzese, Elaine Lockhart, Ian K. Maconochie, and Camilla C. Kingdon — a group consisting mostly of pediatricians (plus Abbruzzese, who is a co-founder of the Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine). Cheung et al. argue that McNamara et al. “was written for a primarily litigious, rather than academic, purpose” — and that this can help explain why it is so misinformed and, in some cases, factually challenged.

I highly recommend that everyone read this paper. But its key insight — or accusation, I should say — is that McNamara and her team really did write their critique as a legal cudgel rather than a traditional academic document. They argue that McNamara et al. employ “a ‘shotgun’ argumentation approach” in which “an argument is made to seem more persuasive not by the quality but volume of arguments (fallacious or otherwise)[.]” This may be “well suited to litigious, adversarial settings,” as Cheung and his colleagues argue, but I would contend that it’s an exceptionally unprofessional and irresponsible approach for actual youth gender medicine researchers and clinicians to take. Frankly put, McNamara and her colleagues have completely mortgaged their own credibility in search of short-term legal wins — and, worse, they are spreading misinformation about serious medical treatments often administered to highly vulnerable youth in a climate of political toxicity and research uncertainty.

Even after this lengthy Part 3, I won’t have gotten to everything in McNamara et al. that deserves critique. As Brandolini’s law tells us, it takes an order of magnitude more effort to refute bullshit than it does to produce it. I’ll be skipping certain (arguably) less important items so that this is merely a long post rather than an unreadably long one.

What an exciting way to end the year(?). Let’s jump right in, picking up from where we left off in Part 2. I did my best to double-check quotes and page numbers — major hat tip to my copy editor, who caught some issues — but as I noted previously, the McNamara and her colleagues made significant changes to this document and republished it without noting those changes, which is wildly out of line with normal academic publishing standards (As I wrote at the time, “When I reached out, Alstott claimed that this was a version-control error and the wrong draft had been posted to the site for a month and a half.”) So there’s a chance a quote or page number from an older version slipped in here. If so, let me know and I’ll fix it.

McNamara and her team write:

Without evidence, the Review states that “practitioners abandoned normal clinical approaches to holistic assessment” (p 13) and that puberty-pausing medications are “available in routine clinical practice.” (p 25) However, the Review’s own data shows that about only 178 youth with gender dysphoria in the UK currently receive medications that pause puberty. It is difficult to see how a medication is both “routine” and only in use by 0.0024% of the adolescent population. [bolding mine, footnotes omitted throughout] [19]

In both cases, McNamara et al. are snipping from longer quotes. On page 13, Cass and her team write that “Some practitioners abandoned normal clinical approaches to holistic assessment, which has meant that this group of young people have been exceptionalised compared to other young people with similarly complex presentations.” First, note that Cass specifically says some clinicians have done this; second, think about the context: This is what Cass and her team found after a yearslong process that included countless interviews, including many with firsthand experience of what was going on at the Tavistock. To accuse Cass and her team of making this claim “without evidence” is deeply disingenuous.

As for the other quote, here it is in full context from the Cass Review:

Preliminary results from the early intervention study in 2015-2016 did not demonstrate benefit. The results of the study were not formally published until 2020, at which time it showed there was a lack of any positive measurable outcomes. Despite this, from 2014 puberty blockers moved from a research-only protocol to being available in routine clinical practice and were given to a broader group of patients who would not have met the inclusion criteria of the original protocol. [25]

It’s clear that “routine clinical practice” simply refers to the transition from the research-only protocol. Cass and her team aren’t making any claims about the frequency with which puberty blockers are prescribed. McNamara and her team are simply changing the meaning of the quote by stripping it of its context.

***

McNamara et al. continue:

The Review’s own data lend insight into how hard it is to access care within the UK’s NHS, and the slow, careful decision making that characterizes this care. First, it reports over two years of waiting for assessment. (p 77) Then, of the 3306 patients seen twice in the GIDS [Gender Identity Development Service] clinic or discharged from April 2018-December 2022, only 27% (892) were referred to endocrinology for consideration and consultation of medical interventions. (p 168) Those referrals were preceded by an average of 6.7 appointments, often with several months between each appointment. Of those seen by endocrinology, 81.5% received puberty-pausing treatment (about half of whom were 15-16 years old which is on the upper end of the age spectrum in which these medications are even usable). [19]

The idea that only 27% of this group was referred to endocrinology is true only in a very narrow, fundamentally meaningless sense. I don’t blame McNamara and her colleagues entirely for getting tripped up here, because I found that the Cass Review presented the results of the “audit” at issue here in a somewhat confusing manner. Then again, as I noted previously, no one from McNamara’s team ever reached out to Cass’s, which would have been a very easy way to clear things up.

The key point here is that so many kids from the audit were lost to follow-up that it’s impossible to draw confident conclusions about this group. As the review itself notes:

The GIDS audit report (Appendix 8) also sets out that 73% (2,415) of the audited patients were not referred to endocrinology by GIDS. Of these:

• 93.0% did not access any physical treatment whilst under GIDS

• 5.0% accessed treatment outside NHS protocols

• 1.5% declined treatment

• 0.5% of patients detransitioned or were detransitioning back to their [birth-registered] gender.

• 69% were discharged to an adult GDC (possibly due to ageing [sic] out of the GIDS service). It is not known how many of these went on to hormone treatment through the adult services. [169]

Elsewhere in the report, Cass and her team note that (in part due to long wait times), a significant number of patients aged out of GIDS to the adult service before all that much could happen, assessment- or treatment-wise. The long wait times were a chronic concern at GIDS that made everything worse, but the point is that if the question is how many of these kids ended up in an endocrinologist’s office, 27% is the lowest possible value for this figure. For 73% of the total number of patients covered by the audit, there’s no record of an endo referral within their GIDS file. But of that 73%, 69% were discharged to the adult service, meaning 1) we have no idea what happened to them, and 2) obviously some percentage of them continued on to medical intervention. If you multiply 73% by 69%, you get 50%, so the actual answer is that, of the 3,306 patients included in this audit:

—27% were referred to endo while in the youth service

—50% were effectively lost to follow-up but remained within the gender-care system

McNamara and her team seemed to have a lot of difficulty understanding this follow-up data problem, even though Cass and her team mentioned it at length — we will return to this later.

***

McNamara and her colleagues write:

The Review claims that these interventions may “change the trajectory of psychosexual and gender identity development.” (p 83) There is no description of how developmental trajectories might be impacted, nor are any data cited. [20]

Again, by stripping the quote from its full context, McNamara et al. make it sound like some sort of out-of-left-field claim. Here’s the full context:

Although it is not possible to know from these studies whether earlier social transition was causative in this outcome, lessons from studies of children with differences in sexual development (DSD) show that a complex interplay between prenatal androgen levels, external genitalia, sex of rearing and sociocultural environment all play a part in eventual gender identity.

Therefore, sex of rearing seems to have some influence on eventual gender outcome, and it is possible that social transition in childhood may change the trajectory of gender identity development for children with early gender incongruence. [32] [paragraph numbers omitted throughout]

It’s very strange to deny the possibility that social transition may alter a child’s developmental trajectory. McNamara and her colleagues argue on the one hand that social transition is vital to a child’s well-being — it’s a deeply meaningful, psychologically potent moment in that child’s young life — but also that it’s impossible for it to have unintended consequences. How could this possibly be the case? It’s an unserious claim. Cass and her team’s claim that social transition might influence gender identity development, on the other hand, is at least buttressed by the DSD research. (No, gender-dysphoric kids usually don’t usually have DSDs, but of course research on DSDs can reveal things about the “complex interplays” at work.)

***

The Cass Review mentions the possibility of desistance, or of kids growing out of their sense of gender dysphoria over time, and cites some studies showing that in certain cohorts, this appeared to be quite common. McNamara and her colleagues do not believe this literature is valid.

They write:

Studies in the 1980s demonstrated that most gender non-conforming children would not meet criteria for gender dysphoria after progression through puberty. These studies inappropriately conflated concepts of gender identity, sexual orientation, and behavior inappropriately. From this arose the concept of “desistance,” meant to describe youth who met criteria for a now outdated diagnosis of “gender identity disorder” as pre-pubertal children but no longer did after they entered puberty. This is not the same as a loss of transgender identity.

Studies that claim high rates of “desistance” in children rely on data collected before there was a formal definition for gender dysphoria. Children’s behaviors were classified as “gender non-conforming” if they did not adhere to gender stereotypes. The Review cites such studies uncritically, even though their findings have no relationship to a contemporary understanding of gender. [italics in original] [21]

This is a distortion of the relevant section of the Cass Review, which reads:

Several studies from that period (Green et al., 1987; Zucker, 1985) suggested that in a minority (approximately 15%) of pre-pubertal children presenting with gender incongruence, this persisted into adulthood. The majority of these children became same-sex attracted, cisgender adults. These early studies were criticised on the basis that not all the children had a formal diagnosis of gender incongruence or gender dysphoria, but a review of the literature (Ristori & Steensma, 2016) noted that later studies (Drummond et al., 2008; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2015; Wallien et al., 2008) also found persistence rates of 10-33% in cohorts who had met formal diagnostic criteria at initial assessment, and had longer follow-up periods. It was thought at that time that if gender dysphoria continued or intensified after puberty, it was likely that the young person would go on to have a transgender identity into adulthood (Steensma et al., 2011). [67]

I don’t know exactly what McNamara and her colleagues mean by “before there was a formal definition for gender dysphoria,” but it seems like they are leaning far too heavily on labels. In the DSM-III, published in 1980, there was a (formally defined) condition called “gender identity disorder.” That label stuck in the DSM-IV. Then, in the DSM-5, released in 2013, it was renamed “gender dysphoria.”

McNamara and her colleagues seem to be alluding to a longtime claim from some trans activists that the desistance studies relied on such lackluster diagnostic criteria that we can’t extract much meaning from them. In a footnote in this section, they write, “ ‘Gender identity disorder’ was eliminated from the DSM-V because this diagnosis pathologized gender nonconformity, which is a natural state of being. ‘Gender dysphoria’ is the most contemporary term and guides our modern understanding of distress related to incongruence between gender identity and one’s physical body.” [21]

The claim that there is an important distinction between the DSM-IV’s and 5’s conceptualizations of gender dysphoria is quite common, but it just isn’t true. It’s a zombie rumor that won’t die. In fact, the criteria between the DSM-IV (gender identity disorder) and DSM-5 (gender dysphoria) are quite similar. I’ve pointed this out repeatedly, including here, and the DSM-IV itself expressly cautioned against diagnosing youth with GID solely on the basis of gender nonconformity.

More recently I spoke to Kenneth Zucker, the author of many of these studies, about this subject (among others). “In terms of the big picture,” he said, “I think the differences across the various editions are error variance.” This is a dressed-up way of saying very small. Now, Zucker is by no means an unbiased observer since it’s his research being attacked, but you really can just read the relevant sections of the DSMs in question and you’ll see that McNamara and her team are significantly exaggerating the supposed shortcomings of the desistance research.

***

Speaking of Ken Zucker: McNamara and her colleagues also write, “Concerningly, despite stating opposition to so-called conversion therapy, the Review favorably cites literature proposing methods that claim to suppress transgender identity in children and uses the ‘desistance’ data from this literature unquestioningly.” [21]

A footnote leads us to this paragraph about Zucker:

Per one such individual: “In my view, offering treatment to a child (either on his or her own or through parental consent) can be justified for a relatively simple reason. Cross gender identification constitutes a potentially problematic developmental condition. Taken to its extreme, the outcome appears to be transsexualism. To make children feel more comfortable about their sex does not, in my view, constitute an unreasonable treatment goal. Although there is considerable disagreement about how one might achieve this aim, the goal itself seems relatively benign.” (Zucker, 1985, p. 117) Zucker, K. J. (1985). Cross-gender-identified children. Gender Dysphoria, 75–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-4784-2_4

Cass and her team cite this study twice, both in the context of simply listing Zucker’s study as presenting one estimate of the desistance rate. It should go without saying that when they cite a 40-year-old paper in one specific context, it does not follow that Cass and her team are endorsing the entire contents of the paper itself.

Should go without saying — but again, remember the shotgun analogy.

***

McNamara and her colleagues write that “The Review’s statements about ‘regret’ and ‘detransition’ are unsupported.”

Let’s take what follows piece by piece. First:

Clinicians who work with transgender people of any age, including youth, follow expert standards of care and adhere to ethical practices that guide them in engaging patients in serious discussions of their full range of options and the associated possible outcomes, including the rare possibilities of regret, treatment discontinuation, and re-identification with birth-assigned sex. And while these outcomes are similar, they are not synonymous. [22]

Which “expert standards of care”? The Cass Review found that the WPATH and Endocrine Society guidelines are woefully inadequate. And how serious could the discussion that, say, Johanna Olson-Kennedy or Jack Turban have with their patients be, given that both of them are opposed to undue assessment and “gatekeeping” of youth gender medicine? Especially in light of the Olson-Kennedy lawsuit?

Continuing:

The Review’s own data contradicts its assertion that “The percentage of people treated with hormones who subsequently detransition remains unknown.” (p 33) In its an [sic] audit of 3,306 patient records from the UK Gender Identity Service, the Review reports that “< 10 patients detransitioned back to their [birth-registered] gender.” (p 168) This is a “detransition” rate of 0.3%. [22]

This is false. The Cheung et al. team that wrote the Archives of Disease in Childhood response lists this 0.3% claim as one of two “[t]wo particularly salient examples” of straightforward “factual errors” in McNamara et al., so I’ll just borrow from them: “The audit included in the Review was of treatment at point of discharge from the Gender Identity Service, so did not include any follow-up data. Hence, no conclusions about detransition rates can be drawn.” Again, the Cass Review makes a point of noting that there is a major problem here: No one knows what happens to these youth once they graduate to the adult services.

Either way, McNamara and her colleagues argue that this is actually in line with other estimates:

The Review’s data is consistent with robust, long-term studies on regret, medication discontinuation and re-identification with birth-assigned sex. Amongst 882 youth with gender dysphoria in the Netherlands who received puberty suppression, 1% discontinued this medication due to resolution of gender dysphoria. Amongst 720 youth in the Netherlands with gender dysphoria who received puberty-pausing medication and gender-affirming hormones, 98% continued gender-affirming hormone treatment as adults. Among 196 youth receiving care in Western Australia’s Gender Diversity Service, 1% who received gender-affirming medications re-identified with their birth-assigned sex. These studies report findings in well-resourced, nationalized health systems where insurance lapses are rare and care is reliably accessible. These studies could have been systematically analyzed by the Review, but they were not. [22]

I’m not going to dig deeply into these studies, other than to say they come from very different contexts than American youth gender medicine (for example, the earliest patients in the Netherlands study were seen in 1972). All I’ll say is that there is a wide range of estimates for detransition, regret, and medication discontinuation, as indicated in this Reuters story. No study is perfect, but one, from a U.S. military healthcare system with good recordkeeping, which seems much more relevant to the present American context, showed that, as Reuters put it, “more than a quarter of patients who started gender-affirming hormones before age 18 stopped getting refills for their medication within four years.” That’s likely an overestimate of the true discontinuation rate for reasons the authors explain, but still: Why is The Integrity Project cherry-picking so severely?

***

More on detransition and regret:

[A] survey of 27,715 transgender adults describes the challenges associated with changes in gender expression. Of the 13.1% who reported “living as [their] sex assigned at birth, at least for a while” after pursuing some form of transition, 82.5% reported familial pressure, social pressure, employment difficulty, inability to access care, and financial reasons as influential factors. These reasons do not pertain to a change in identity, but rather the systemic and structural social forces that stigmatize and ostracize transgender people.

. . .

Rather than consider these studies, the Review relies research [sic] plagued by poor methodology, heavy selection bias, and sampling from anti-transgender websites. In many of the studies it cites, “detransition” is vaguely defined and incorrectly conflated with discontinuing treatment. The Review criticizes and ultimately discards numerous rigorous research studies on transgender identity and medical treatments for gender dysphoria in youth, while confidently citing pseudoscience in support of outdated and debunked notions around rare phenomena like regret after gender-affirming care. In considering the value of the Review’s contributions to the field of transgender health, this discrepancy should not be overlooked. [22–23]

We have no idea if this is a “rare phenomena” because there are very few studies, they offer very different answers, and almost none of them cover contemporary youth who have physically transitioned.

The data McNamara and her colleagues cite approvingly is from the 2015 United States Transgender Survey. The USTS’s authors note that it is a “a purposive sample that was created using direct outreach, modified venue-based sampling, and ‘snowball’ sampling. As a non-probability sample, generalizability is limited and the USTS sample may not be representative of the broader transgender population in the U.S.” It is also a survey of people who currently identify as trans, meaning there is zero reason to think it can be used to generate a meaningful estimate of the rate at which some people who transition durably detransition. (See here for an explanation of snowball sampling.)

McNamara accuses Cass of “[relying on] research plagued by poor methodology, heavy selection bias, and sampling from anti-transgender websites.” A footnote explains that “Littman 2018 was an anonymous online survey of 100 ‘detransitioners’ who were recruited on social media, professional listservs, and snowball sampling. Many online communities for detransitioned individuals have been co-opted by anti-trans social media users, including the subreddit Littman references r/detrans. With these sampling and recruitment methods, there is a high risk of bias.”

So in consecutive paragraphs, McNamara and her colleagues endorse the use of an online survey generated (in part) via snowball sampling — a survey of currently transitioned individuals — as providing meaningful data about detransitioned individuals, only to turn around and knock a survey drawn from a subreddit as unacceptable because of its sampling issues — including snowball sampling — and high risk of bias. (Oh, and also, it’s been infiltrated by transphobes.) To be clear, neither study gives us particularly sturdy, reliable information about the subject at hand, and Littman’s is simply an early, exploratory attempt to gather some data about detransitioners. But again, the double standards jump off the page — the only goal of McNamara and her team is to bash the Cass Review from any angle imaginable. Principles and consistency would complicate their efforts.

It’s also worth noting that in the actual Cass Review, Cass and her colleagues describe the Littman survey in an appropriately careful way. After having noted that we know very little about detransitioners, they describe the method as “A self-identified sample of 100 detransitioners (Littman, 2021) completed an anonymous online questionnaire.”

***

McNamara et al. also direct unfair macro-level complaints about the systematic review process underlying the Cass Review:

The York team used a single search strategy for all SRs, which likely excluded many relevant studies in each of the specific areas. [30]

This is a strange claim. The York team members did, in fact, engage in a big, broad search for all the literature it could find on transgender and/or gender-dysphoric youth, as laid out here. Then, for each of the systematic reviews, it went through the extracted studies to determine which were relevant to the review in question.

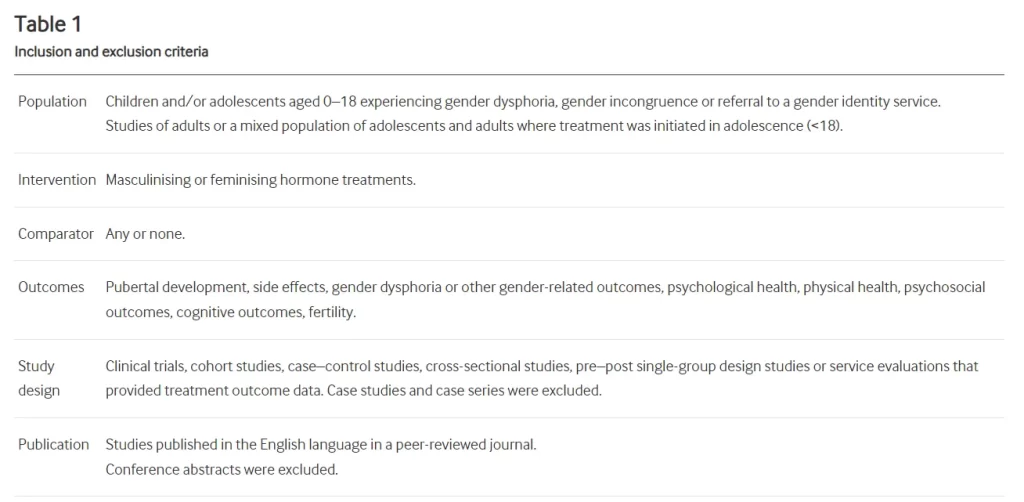

For example, the systematic review on hormones looked for studies from this mega-list on the basis of these inclusion and exclusion criteria:

It’s unclear why McNamara and her co-authors think that a search that was specifically designed to be big and broad “likely excluded many relevant studies in each of the specific areas.” Any study that was about kids or adolescents and gender dysphoria and/or gender identity, and that also met the inclusion criteria for the specific review in question, would be included.

***

McNamara et al. express frustration that “in some cases, recommendations for clinical care were made by the SR authors themselves in the SRs themselves” [37]. They actually cite just one example in a footnote — this paragraph from the hormones SR:

Clinicians should ensure that adolescents considering hormone interventions are fully informed about the potential risks and benefits including side-effects, and thelack of high-quality evidence regarding these. In response to their own evidence review, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare now recommends that hormone treatments should only be provided under a research framework, a key aim for which is to develop a stronger evidence base. As they point out, this approach is common practice in other clinical specialties, where to receive treatments for which the benefits and risks are uncertain, patients must take part in research.

To be clear, this really isn’t much of a clinical recommendation. Maybe you could accuse the authors of straying a little beyond their purview, but they’re barely recommending anything other than informing patients of risks and benefits of a treatment, which is supposed to be something responsible doctors do anyway.

Either way, two pages earlier McNamara and her team positively cite a WPATH-sponsored systematic review on hormones for having the appropriate level of independence and firewalling, though they don’t mention that its lead author, Kellan Baker, is also a co-author on this very response.

They include this quote from that SR:

WPATH provided the research question and reviewed the protocol, evidence tables, and report. WPATH had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or drafting. . . The authors are responsible for all content, and statements in this report do not necessarily reflect the official views of or imply endorsement by WPATH. [36]

It’s bizarre McNamara et al. included this, because thanks to documents turned up in a legal case, we now know this claim is almost certainly complete bullshit, and WPATH in fact interfered heavily with the process. (Read my article in The Economist for more on this.)

Either way, that same systematic review first concludes that while there are studies linking hormones to some beneficial outcomes, those studies are weak, and there aren’t enough quality studies to render any verdict on suicidality. Baker and his colleagues then weirdly tout the benefits of hormones. “These benefits make hormone therapy an essential component of care that promotes the health and well-being of transgender people,” they editorialize.

By the standards of McNamara and her colleagues — one of them Kellan Baker himself! — this is a “clinical recommendation,” which is totally inappropriate for a systematic review to include. Until it isn’t. Rules? What rules? This is basically Calvinball, except it’s not a young boy playing it, but highly credentialed experts who are trusted by countless Americans to accurately communicate the contours of this controversy.

***

McNamara and her team write that “Medications to pause puberty have long been used for central precocious puberty without negative impact on cognitive development.” [26]

It’s amazing that this claim is still floating around. The whole point is that if you put a kid on blockers and then cross-sex hormones, that is a very different development trajectory, because 1) they are usually going on blockers later, and 2) in most cases, they are not simply ceasing blockers so their natal puberty can take over, but rather going through a puberty based on cross-sex hormones. There are all sorts of questions about whether they will subsequently “catch up.”

Almost nothing from the evidence base for the treatment of precocious puberty can be neatly applied to the debate over youth gender medicine.

***

In a discussion of the sizable increase in referrals to youth gender clinics, McNamara and her team say this:

The Review repeatedly describes “peer and socio-cultural influence” as driving the increase in referrals. The theory that such factors influence gender identity development in youth originates from a single article that has been heavily corrected for numerous well-documented fatal flaws. Using sound methods, no link has been found between peer influence and gender identity development. [23–24]

It’s simply false that this article, Lisa Littman’s 2018 report on the proposed concept of rapid-onset gender dysphoria, was “heavily corrected.” Rather, PLOS One, responding to a firestorm from activists, made various alterations to the article to ensure it contained enough context. PLOS One confirmed to me at the time that there were zero corrected factual errors in the article itself.

It’s also frankly ridiculous to claim that before Littman came along, no one thought that peer and socio-cultural influence affected gender identity development. This is not a new idea. Take, for example, the following paragraph from the introductory chapter to a 2018 book called The Gender Affirmative Model: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Supporting Transgender and Gender Expansive Children. It’s written by Colt Keo-Meier and Diane Ehrensaft, two clinicians seen as staunch defenders of trans kids and the gender-affirming approach:

Ehrensaft (2011, 2016) created the concept of the gender web to guide viewing of the children. The gender web is a four-dimensional structure, the three material dimensions being nature, nurture, and culture, and the fourth dimension being time. Imagine a spider web stretched out in a tree to get the visual image, a web that may change its dimensions over time as the spider enhances its home. The gender web is each child’s personal creation, spinning together the three major threads of nature, nurture, and culture that interface to allow the child to construct a gender self. Like fingerprints, no two individuals’ gender webs will be exactly the same; unlike fingerprints, the gender web is not immutable—it will inevitably change over time. While people are little, to promote individual gender health, defined as freedom to explore and live in the gender that feels most authentic, the only person who should be doing that spinning is the child. [emphasis in the original]

Keo-Meier and Ehrensaft then explain that part of the theoretical basis for the gender-affirming model is that “according to current knowledge, gender involves an integration of biology, development and socialization, and culture and context, with all of these bearing on any individual’s gender self.”

The “culture” part of the web has gotten a lot more complicated in the age of social media and rapidly shifting norms about sex and gender identity. The claim that these external factors have no impact on adolescents’ sense of their gender identity is an extremely radical theory from a developmental psychology perspective. I’m not saying McNamara and her colleagues shouldn’t be allowed to posit this theory, of course — I’m just saying that their claims should be treated with extreme caution until sound evidence is provided. To argue that “Using sound methods, no link has been found between peer influence and gender identity development,” McNamara and her colleagues cite this study published in The Journal of Pediatrics. But you can see from these response letters (one by Littman herself) that the study doesn’t come close to providing conclusive answers to this question.

In addition to the above, many clinicians themselves are seeing cases of gender dysphoria in which peer influence seems to play a role — I’ve spoken with plenty of them, and some, foremost among them Erica Anderson and Laura Edwards-Leeper, have discussed this publicly.

***

McNamara and her colleagues accuse the Cass team of fearmongering about puberty blockers’ effects on “adolescent cognitive development,” even as they acknowledge that much remains unknown about this topic. Overall, they argue that “The currently available evidence does not support the Review’s concern.”

They write:

The largest and longest study on this topic showed that intelligence quotient and educational achievement amongst youth receiving puberty-pausing medications did not substantially differ from a population of similarly aged Dutch teens. The York SR on puberty-pausing medications misrepresented the evidence by failing to include this study, and also erroneously reported that “the only study [on puberty-pausing medications and cognition] showed worse executive functioning at > 1 year. . . ”. This latter study actually showed significantly better executive functioning in those receiving gender-affirming hormones compared to puberty-pausing medications. Executive functioning was worse amongst those who received puberty-pausing medication for a long time compared to those who received gender-affirming hormones earlier. The appropriate conclusion is not that puberty-pausing medications worsen executive function: rather, it is that cognitive development of transgender youth may be affected in concerning ways by prolonged delays before affirming physical changes with appropriate treatment. [25–26]

Is it “misrepresenting the evidence” to exclude a study? Of course it isn’t. In this case, the systematic review explains that the team searched for studies in April 2022. The “largest and longest” study in question was published after that. Should it have affected the York team’s overall view of the literature? Almost certainly not. It concerned only Dutch young people who had had puberty blockers, hormones, and bottom surgery, and it had no genuine comparison group (at various points the authors compared members of this cohort’s scores to average Dutch statistics, which for many reasons is not a clean comparison). The authors of that study themselves explain that “this study had only two measurement points and could therefore not differentiate effects from either PS [puberty suppression] or GAHT [gender-affirming hormones treatment] alone.” So in all likelihood, the York SR team would not have rated it highly, simply because it wasn’t built to isolate the effects of puberty blockers, and because of major potential for sampling bias — any youth experiencing serious mental or physical health outcomes would have been excluded outright from transitioning under the Dutch protocol, or would not have made it all the way through to bottom surgery.

As for McNamara and her team’s claim that Cass and hers “erroneously reported” the results of another study, the quote “the only study [on puberty-pausing medications and cognition] showed worse executive functioning at > 1 year. . . ” does not appear in the systematic review on puberty blockers in any form. I think the excerpt McNamara and her colleagues are attempting to quote is “One cross-sectional study measured executive functioning and found no difference between adolescents who were treated for < 1 year compared with those not treated, but worse executive functioning in those treated for > 1 year compared with those not treated.” There is nothing “erroneous” here. This systematic review was on blockers, not hormones, so the authors reported what the study found about blockers. Sure enough, the SR on hormones includes that very same study (see footnote 45 in the hormones SR).

Again, these are really basic errors about systematic reviews that McNamara and her team are making.

***

The Cass Review has this to say about puberty blockers:

The systematic review undertaken by the University of York found multiple studies demonstrating that puberty blockers exert their intended effect in suppressing puberty, and also that bone density is compromised during puberty suppression.

However, no changes in gender dysphoria or body satisfaction were demonstrated. [32]

McNamara and her colleagues are greatly frustrated by this passage. They write:

Here, the Review expresses the expectation that an intervention would lead to an outcome that experts in youth gender care do not: experts do not expect lessened gender dysphoria or increased body satisfaction with puberty-pausing medications alone, because these medications do not change the current physical characteristics of one’s body. They only prevent future changes. Puberty-pausing medications only pause development of puberty-induced characteristics that might be detrimental to the psychosocial well-being of a transgender young person. For example, puberty-pausing medications halt growth of breasts, but they do not reverse any breast growth that has already occurred; puberty-pausing medications can prevent the deepening of one’s voice, but they will not raise the pitch of a voice that has already deepened.

The Review’s implication that puberty-pausing medication should lead to a reduction in current gender dysphoria or improve one’s current body satisfaction indicates ignorance or misunderstanding at best, and intentional deception about the basic function of these medications at worst. In an era of abundant misinformation, it is important remember [sic] the exact function of these medications. The Review, as a document of such influence and importance in the field of transgender health, should not operate from any position of ignorance about this care. [27]

This is perhaps the most galling, unprofessional, and dishonest passage of McNamara et al. — and if you’ve read this far, you recognize how crowded the field is.

Here’s Johanna Olson-Kennedy, one of the McNamara et al. co-authors, in a research protocol for one of her own studies1: “Hypothesis 1a: Patients treated with GnRH agonists [puberty blockers] will exhibit decreased symptoms of gender dysphoria, depression, anxiety, trauma symptoms, self-injury, and suicidality and increased body esteem and quality of life over time.” And here, one more time, is what she co-wrote in the Yale document: “The Review’s implication that puberty-pausing medication should lead to a reduction in current gender dysphoria or improve one’s current body satisfaction indicates ignorance or misunderstanding at best, and intentional deception about the basic function of these medications at worst.”

So Olson-Kennedy, whose team is the recipient of millions of government dollars for their research on the outcomes of trans youth, hypothesizes that blockers will reduce gender dysphoria and improve “body esteem.” Then she turns around and accuses Hilary Cass and her team of “ignorance or misunderstanding at best, and intentional deception. . . at worst” for considering this very hypothesis. I can only use the term unprofessional so many times, but this is above and beyond.

And Olson-Kennedy wasn’t the only researcher to posit this hypothesis! The events leading up to the Cass Review included a somewhat byzantine controversy over data that GIDS appears to have attempted to suppress and released only as a result of a court order. That data showed that contrary to prior claims that had come out of the clinic, puberty blockers did not improve young people’s mental health. One of those prior claims was that “early intervention is also associated with a reduction in the gender dysphoria experienced by these adolescents.”

***

McNamara and her colleagues accuse the authors of the Cass-commissioned systematic reviews of registering one set of methods in their protocol and then switching to another, jeopardizing the integrity of the entire project:

In the pre-registered protocol, the SR team planned to appraise the quality of studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). However, they switched to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), but with several adaptations performed by the York SR authors. In their published SRs, they neither mention nor justify this deviation from their protocol. This is a divergence from standard practices designed to minimize bias in systematic reviews and it is not a minor one. This change may have had a decisive impact on the conclusions in the York SRs. In particular, the developers of the MMAT encourage SR authors to include all studies in analysis. Using NOS and the arbitrary cutoff that the York SR authors determined, only a portion of the evidence was considered. This is discussed in greater detail as we describe use of the quality appraisal tool below. [29–30]

The basic facts here are correct. If you go to the Prospero protocol, you’ll see that between the June 21 and July 10, 2024 versions, the researchers added an explanation as to why they changed measures (search down to “Risk of bias (quality) assessment”). This suggests, but doesn’t prove, that they added this explanation in response to McNamara and her team pointing out that the switch had, as of when their critique was published July 1, gone unexplained.

So no, not ideal. They should have been more transparent. But the idea that this particular switch from one assessment tool to another, “may have had a decisive impact on the conclusions of the York SRs” has no real basis to it.

First, every government-sponsored systematic review ever conducted on this subject has come to the same conclusion: The evidence is weak. So it’s hard to argue that the Cass team found what it found because of their particular choice of instrument, unless all the other, similar efforts made similar errors with regard to instrument choice. (And remember that no one on the McNamara et al. team has expertise in systematic reviews, so that would be quite a find on their part.)

Second, here’s how Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, an epidemiologist who believes there are major problems with the Cass Review, addressed this particular issue in one entry from his seven-part (!) series critiquing the document:

There’s a belief going around online that the reason that the reviewers switched the scales is because the MMAT recommends against excluding low quality work, while the NOS has no such recommendation.

As someone who does systematic reviews professionally, this argument makes no sense to me. All rating for bias is to some extent subjective. While both the MMAT and NOS attempt to create some measure of objective ranking for research, they are both ultimately up to the judgement of the reviewers who are using the tools. Changing your rating scale isn’t going to magically change the conclusions of a systematic review, especially when the review uses a narrative (i.e. subjective) synthesis method anyway.

In addition, as I noted above, including low quality studies in these reviews probably wouldn’t change much, because the low quality of the papers reduces their usefulness anyway. I very much doubt that anyone cared enough about the rating scale to switch it for nefarious reasons — the most likely explanation is that they didn’t find many qualitative studies in their searches. It’s not best practice that the reviews don’t explain the differences between their registration and the publication, but on the scale of academic crimes this barely rates as a misdemeanor.

Gordon Guyatt, one of the godfathers of evidence-based medicine, agreed that this sort of change is not unusual. “We change all the time,” he said of his own work on systematic reviews. He explained that “In our experience, when you start doing the work, you find stuff you weren’t expecting or fully anticipating, and that warrants changes.” The issue is whether the change was “adequately justified,” and McNamara and her team don’t make a compelling argument otherwise, at least according to Meyerowitz-Katz. Guyatt pointed out that these sorts of changes to pre-established protocols are concerning when, for example, you pick one set of outcome variables at the outset, and then switch them without explanation. (Ironically, Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues appear to have done exactly that in their most famous study about youth gender medicine, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.)

The same logic applies to the criticism that the Cass SRs excluded non–English language and “gray” (unpublished) literature, which McNamara and her colleagues allude to when summarizing the work of another team of activism-oriented Cass-review critics [33]: Might this be a problem in some contexts? Sure. Is there any evidence it would meaningfully change the results of this particular effort? No. “The issue is, how likely is it [that] important information, evidence, was left out” due to the exclusion of non–English language results, Guyatt explained. “My instinct is it’s pretty unlikely. In other words, the critique would be much more compelling if they say, And by the way, we looked at the non–English language literature, and there’s some important stuff that’s been left out.”

As for the file drawer, McNamara and her team (and the aforementioned other team) seem to be saying that there might be a lot of positive results that got file-drawered, and that the York team missed out on them by not searching for this subset of papers. All I’ll say is that I find this exceptionally unlikely given that it’s usually nonsignificant results that get tossed in the file drawer — that’s often how the “file-drawer problem” is defined! — and given the demonstrably low barrier to publication for very weak papers that superficially appear to provide support for youth gender medicine, including in major journals like NEJM and Pediatrics.

Maybe I spent too much time on this, but “An Evidence-Based Critique of ‘The Cass Review’ on Gender-affirming Care for Adolescent Gender Dysphoria” is a calumnious 30-car pileup of scientific misinformation. It offers an ugly, remarkably messy case study on what happens when highly credentialed, trusted experts simply stop caring about the truth, when they let the pull of political righteousness guide them instead. Legitimate disagreement is one thing, but a paper this flawed and this dishonest should leave a mark on any institution or scientist who promotes it. It’s really that bad. Yale Law School should be exceptionally careful about promoting the work of “The Integrity Project” going forward.

A final note: In October, I sent McNamara and Alstott a brief email explaining that I planned to write more about their white paper, and asking them about two claims from their paper that appear to be clearly, indisputably false: “An assertion that the Cass Review highly ranked the quality of WPATH guidelines” (as I addressed in Part 1), and “A claim that the audit data reported by the Review demonstrate a detransition rate of 0.3%.” I also forwarded the email to Aron Janssen, simply because I know him a little bit and have interviewed him before.

This seems like the lowest possible bar for public intellectuals to clear: Once you and your co-authors have published false claims, what do you do about it? Do you correct the claims? If your co-authors refuse to, do you yank your name off the paper?

No one got back to me. The paper is still sitting there on Yale Law School’s website, no changes, same authors.