For our third article about the problems with the Yale Integrity Project, we share this critique by Jesse Singal. Republished here in full with the permission of the author. He makes similar points to those highlighted by FDNHSA about the conflict of interest of the authors and also provides important commentary about the Yale “Integrity” Project’s misleading statements about the rapid rise in referrals to the gender clinic in the UK.

Originally published on Jesse Singal’s substack, Singal-Minded here: https://open.substack.com/pub/jessesingal/p/yales-integrity-project-is-spreading?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web]

Yale’s “Integrity Project” Is Spreading Misinformation About The Cass Review And Youth Gender Medicine

Part 1 of a two-parter that is not going to increase your faith in highly credentialed experts

Aug 19, 2024

Back in April, the National Health Service published the Cass Review, an ambitious effort to evaluate and reform the UK’s provision of youth gender care. The effort was led by Hilary Cass, a highly respected, retired pediatrician.

Among other goals, Cass and her team sought to conduct a sweeping evaluation of the evidence for youth gender medicine by commissioning a University of York team to conduct a series of systematic reviews. As Cass and her team wrote in the final document, these reviews found that there is “remarkably weak evidence” to support youth gender medicine. Now, by the time the review was published, the NHS had already effectively banned the use of puberty blockers as a treatment for gender dysphoria and tightened the policies surrounding the prescription of cross-sex hormones to gender-dysphoric youth, introducing a loose age guideline that stated teens shouldn’t receive hormones until “around” their 16th birthday. But of course the Review further legitimized those decisions. (You can read my initial thoughts on the document here.)

On the one hand, the Cass Review sent shock waves throughout the world of youth gender medicine, simply because it was such an ambitious and clearly professional effort. On the other hand, it wasn’t a surprise to those who have been following this controversy, since so many other government-sponsored reviews of the evidence — including from Finland, Sweden, Norway, and the UK itself — had all come to similar conclusions about youth gender medicine. (The Cass Review also examined the evidence for youth social transition and came to the same conclusion.)

The Cass Review was met with a predictable burst of misinformation from certain prominent online activists and their followers, who sought to undermine its findings. Many of the false claims these figures propagated, such as the idea that the authors of the systematic reviews excluded 98% of the studies they initially assessed, were fairly easily debunked (including, in some cases, by the Review team themselves in a follow-up FAQ), and didn’t really seem to penetrate the public conversation.

Since then, though, a more disturbing trend has emerged: Otherwise respected, well-credentialed experts have begun disseminating blatant misinformation about seemingly every facet of the Cass Review and its findings. The worst example of this, by far, was a July 1 white paper published by The Integrity Project, a Yale Law School organization. It’s titled “An Evidence-Based Critique of ‘The Cass Review’ on Gender-affirming Care for Adolescent Gender Dysphoria.”

This white paper has spread far and wide, and has been treated by some as a definitive debunking of the Cass Review. Writing in a New York Times article that was highly critical of the Cass Review, Lydia Polgreen positively referenced and linked to the white paper, noting that it was authored by a team that included “two Yale professors.”

The paper’s authors are Meredithe McNamara, Kellan Baker, Kara Connelly, Aron Janssen, Johanna Olson-Kennedy, Ken C. Pang, Ayden Scheim, Jack Turban, and Anne Alstott. Some of these names are quite familiar to those who have been following this subject: Janssen and Olson-Kennedy are longtime youth gender medicine providers (both of whom I quoted in my longest feature story on this subject), and Turban is a younger gender clinician and frequent commentator on these issues as well as the author of a new book touting the importance of “affirming” youth, both socially and medically. The paper’s lead author, Meredithe McNamara, is an adolescent medicine physician at Yale Medical School who has carved out a very prominent role in the national conversation. Her Integrity Project co-founder, Alstott, is a highly respected legal scholar at Yale Law School.

This paper, which has not been peer-reviewed, purports to reveal extremely serious weaknesses in the Cass Review. The authors write early on:

As researchers and pediatric clinicians with experience in the field of transgender healthcare, we read the Review with great interest. The degree of financial investment and time spent is impressive. Its ability to publish seven systematic reviews, conduct years’ worth of focus groups and deeply investigate care practices in the UK is admirable. We hoped it would improve the public’s awareness of the health needs of transgender youth and galvanize improvements in delivery of this care. Indeed, statements of the Review favorably describe the individualized, age-appropriate, and careful approach recommended by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the Endocrine Society. Unfortunately, the Review repeatedly misuses data and violates its own evidentiary standards by resting many conclusions on speculation. Many of its statements and the conduct of the York SRs reveal profound misunderstandings of the evidence base and the clinical issues at hand. The Review also subverts widely accepted processes for development of clinical recommendations and repeats spurious, debunked claims about transgender identity and gender dysphoria. These errors conflict with well-established norms of clinical research and evidence-based healthcare. Further, these errors raise serious concern about the scientific integrity of critical elements of the report’s process and recommendations. [emphasis in the original throughout this article, citations omitted throughout, and when quoting from the McNamara document I’ll indicate page numbers with brackets] [2]

Yale Law School published a press release accompanying the white paper highlighting its level of rigor. Just about anyone who reads McNamara and her co-authors’ article and examines the qualifications of the authors will conclude that there is so much smoke here that there simply must be fire — something must really be wrong with the Cass Review for it to have elicited such a searing rejoinder from such an august group of academics.

But McNamara et al. is an exceptionally misleading, confused, and fundamentally unprofessional document. The authors make objectively false claims about the content of the Cass Review, badly misrepresent the present state of the evidence for youth gender medicine, and, just as alarmingly, exhibit a complete lack of familiarity with the basic precepts and purposes of evidence-based medicine. In some cases, the errors are so strange and disconnected from the Cass Review that they can only, realistically speaking, be attributed to malice, a severe lack of curiosity and reading comprehension, or both. This might sound harsh, but you’ll see what I mean shortly. It is genuinely surprising that any of the co-authors would agree to put their names on a document like this.

I was hoping to speak with McNamara to ask her about this white paper, but an emailed interview request to two Yale press staffers garnered no reply. In addition, I reached out to Aron Janssen via email but didn’t hear back. The Cass Review team was more responsive, but only to a point: In July a spokesperson answered some of my questions via email, but then, when I sent them a final list of questions last week, they told me that Cass and her team were holding off on issuing any further statements to the media until the publication of a peer-reviewed response that is being prepared by a separate group. That’s why you’ll see, in what follows, that in some but not all instances I was able to get a direct response from a Cass Review spokesperson.

This was a very difficult response to organize simply because of how many false and wrongheaded claims are in McNamara and her team’s 37-page white paper. I ultimately decided to split it into two parts. This one will summarize the McNamara team’s many undisclosed conflicts of interest and their document’s key factual errors about the content of the Cass Review. Part 2 will get a bit more into the weeds, examining instances in which McNamara and her colleagues badly misrepresent or misunderstand evidence-based medicine (EBM), the present state of youth gender medicine research, or both. (I will offer a quick primer on EBM in Part 2, but it won’t be necessary to understand this article.)

To be clear, even at its considerable length, this isn’t a totally comprehensive response. If I missed anything big, and a reader points it out to me, I might add it as an update. I’m also not going to reflexively defend the Cass Review, of course. For transparency’s sake, given how critical I’m being of the McNamara team, it’s also quite important to note that they do land some fair blows, as I’ll indicate when warranted.

Overall, though, the legitimate critiques leveled by McNamara and her colleagues are dramatically overshadowed by the unfair ones, and none of them come close to threatening the validity of the Cass Review’s core claims about the lack of evidence supporting youth gender medicine. In full context, these legitimate criticisms mostly come down to nitpicking — nitpicking accompanied by what is, to be frank, a large quantity of highly questionable claims.

I ran significant segments of what follows by Dr. Gordon Guyatt, one of the godfathers of evidence-based medicine and an expert when it comes to the methodologies in dispute here. His responses were quite helpful, and you’ll see that I quote him throughout.

The Entire White Paper Is Ethically Troubled Due To The Authors’ Lack Of Disclosure Of Their Numerous Conflicts Of Interest And Meredithe McNamara’s Misleading Public Statements About Her Own Expertise

McNamara and her colleagues accuse the process behind the publication of the Cass Review of lacking transparency, writing that “many of the Review’s authors’ identities are unknown. Transparency and trustworthiness go hand-in-hand, but many of the Review’s authors cannot be vetted for ideological and intellectual conflicts of interest.” They also write that “The transparency and expertise of our group starkly contrast with the Review’s authors.” [3]

In the above quote, “unknown” has a footnote leading to this:

Following the completion of the “research programme” by the University of York, “A Clinical Expert Group (CEG) was established by the Review to help interpret the findings” (p 26), defined as “clinical experts on children and adolescents in relation to gender, development, physical and mental health, safeguarding and endocrinology” (p 62). There is no further information about the qualifications of the members of the CEG, nor how they were selected.

The CEG comes up throughout the Cass Review, and Guyatt said he agrees with McNamara and her colleagues about this. “That is a substantial problem that you don’t even say who the experts you consulted are,” he said. He pointed out that youth gender medicine is “a polarized community. Presumably, you would want all credible views to be represented, and it would not be difficult to pick and choose. Were you to have decided what you wanted to say in advance, it would not be difficult to pick a restricted range of experts.” The point isn’t that Cass and her team did cherry-pick in this manner, but rather that by not disclosing the members of the CEG, it opens them up to that accusation — there’s no way to know.

Now, we do know the authors of the systematic reviews themselves, which were the most scientifically important output of the Cass Review by far, especially from an international perspective. So this transparency problem doesn’t really bear on those results, and doesn’t change the fact that the evidentiary landscape is so grim.

Long story short, though, this is a fair critique, and something I would have loved to have asked the Cass team about. But on the other hand — and it is a big other hand — it’s strange that McNamara and her team would level this accusation and then fail to disclose any of their own myriad conflicts of interest.

Let’s start with some of the authors’ roles as paid expert witnesses for parties fighting American bans or restrictions on youth gender medicine: McNamara ($400 per hour), Janssen ($400 per hour), Olson-Kennedy ($200 per hour), and Turban ($400 or $250 per hour, depending on the task) have all received money as expert witnesses in cases fighting bans or restrictions of youth gender medicine in American states. If someone gets paid as an expert witness, does that mean we should never trust them? Of course not. But it does mean that they need to disclose this when appropriate, especially when they are touting the “transparency” of their work. In other cases, co-authors on this document also have consulting and textbook royalty income riding directly on the continuing availability of youth gender medicine, which of course also bears mentioning.

Moreover, multiple studies published by Turban were rated as low quality by the Cass team’s systematic reviewers. One of Turban’s studies (footnote 53) was deemed low quality in the SR on puberty blockers; another (footnote 65) was deemed low quality in the SR on hormones (if you’re a subscriber to this newsletter, the weaknesses of these studies will not come as a surprise). Three of Olson-Kennedy’s studies were rated “moderate” in the puberty blocker and hormones SRs. This warranted disclosure as well, because readers have a right to know about these sorts of conflicts: Here Turban is co-authoring a searing assessment of a project that rated his own work poorly. Guyatt agreed that the expert witness, royalty, consulting, and authorship conflicts should have been disclosed.

Finally, there’s the simple fact that a number of the authors work in gender clinics. They tout this rather than hide it (albeit without mentioning, by name, who works in gender clinics), and to be fair, this isn’t usually considered a conflict of interest. But it really should be: If you work in a youth gender clinic, you are obviously conflicted when it comes to evaluating a document that rates the evidence for youth gender transition poorly! How can anyone even contest this? I asked Guyatt and he agreed both that this isn’t usually seen as a conflict and that it should be.

I want to linger on this for a moment because I think it’s exceptionally important for understanding this debate, which centers on scientific papers that are overwhelmingly published by individuals who work in, or in close consultation with, youth gender clinics. When I asked Guyatt why there isn’t a norm in favor of this sort of disclosure, he argued that it’s a bit of a holdover from the bad old days:

Now you’re asking me a sociological question, and I’m not a sociologist. However, what I can say is that the tradition of people making guidelines, going way back, has been to pick people who are leaders in their field. And we had a name for this approach that we call GOBSAT, which is “good old boys sitting around a table.” And that has been the tradition, and these experts would be typically people who would be delivering care at, presumably, the highest levels of people with the particular condition in the particular way that they deliver care. And so it would be quite natural in one way of looking at it: Oh, look, these people deliver care to thousands of patients that are the sort of patients of interest. They must know what they’re doing, and they are the people we should go to. And on the surface, that sounds like not unreasonable logic, until, as you point out, you take the next step, that if you’re delivering care in this particular way, you’re making money out of it, you have an investment in believing that delivering care in this particular way is the best way to deliver care.

I want to be clear that the argument here is a bit more nuanced than a straightforward financial conflict of interest. It’s also that if you’re a clinician delivering this care, you’re probably doing so because you think it works. You think you’re helping your patients! Why else would you do it? So there’s an intellectual or cognitive-dissonance element, too, to the argument that this should be considered a conflict of interest.

Whether or not the members of the McNamara team who work in gender clinics should have listed that work as a conflict, the fact is that they didn’t list any of their many conflicts — including those that are routinely disclosed — and that they do have direct financial, intellectual, and professional incentives to gainsay any document that casts their work in a negative light. This, again, does not mean we shouldn’t trust their claims, because it’s perfectly possible to both be conflicted and correct (I don’t like Donald Trump, but that obviously doesn’t mean that every claim I make about him is false). But to not mention any of this, all while complaining about another team’s lack of transparency and rigor, is unprofessional.

***

One person who doesn’t work in a gender clinic is Meredithe McNamara. You might not know that, given that over and over and over, she has written and said things that seem to strongly suggest otherwise. This is one of the strangest subplots of The Integrity Project and its response to the Cass Review.

As Leor Sapir summed up recently, in a short period, McNamara has become an extremely prominent voice advocating for youth gender medicine. She shows up everywhere, from TV interviews to expert witness declarations to peer-reviewed academic articles and testimony before lawmakers. Over and over and over, she presents herself as having direct experience treating gender-dysphoric youth.

Sapir writes:

- In testimony before the Florida medical boards in 2022, McNamara said that she “provide[s] clinical care for youth ages 12 to 25, which includes transgender and gender expansive youth.” When asked by one of the medical board members about her experience referring minors for gender surgery, McNamara responded: “I’ve never referred a patient for surgery because a patient has never desired surgery who[m] I’ve cared for. It’s all about what the patients wants [sic], [and] how that fits into the informed consent model. . . . None of my patients had desired that surgery at that moment in time. We discuss [it] openly.”

- In an interview with Chris Cuomo on NewsNation in December 2022, McNamara described herself as “deeply ingrained in this professional community.” When Cuomo asked how she manages the concerns of parents, McNamara responded that she “invite[s] parents to be a part of every single conversation in every stage of it. . . . And, we say. . . one thing that I like to say is, ‘what does it cost you, to just affirm who they say they are?’ ”

- A 2022 report McNamara coauthored with colleagues at Yale School of Medicine and the University of Texas Southwestern introduced the authors as medical professionals who “all treat transgender children and adolescents in daily clinical practice” (emphasis added). Later in the report, when the authors dispute the credibility of the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine (SEGM), McNamara and her coauthors emphasize that “none [of SEGM’s members] currently treat patients in a recognized gender clinic.”

- In a medical journal article titled “Combatting [sic] Scientific Disinformation on Gender-Affirming Care,” McNamara and her coauthors characterize themselves this way: “All [are] clinicians [who] treat transgender youth and practice in jurisdictions of GAC bans.”

- In the Georgia lawsuit Koe v. Noggle, in which she is an expert witness, McNamara declares in her expert report: “I provide full spectrum clinical care to youth aged 12-25 years, which includes youth experiencing gender dysphoria.”

- In a Boston Globe op-ed from March, McNamara called herself “a pediatrician who serves youth with gender dysphoria” and “who cares for transgender youth.” She writes that “one thing in common that I see universally in the care of transgender youth” is that “decisions on whether, when, and how to pursue medical interventions are slow-moving, rigorous, and individualized.”

But in a recent sworn deposition, McNamara acknowledged that she actually has no clinical experience working with this population.

Sapir, again:

On April 4, as part of her role as expert witness in Boe v. Marshall, a lawsuit challenging Alabama’s age-restriction law, McNamara submitted to an eight-hour deposition. The transcript of that deposition reveals that McNamara’s many public and under-oath statements about her clinical experience are fundamentally misleading, if not outright false—and even perjurious.

As it turns out, McNamara admits that she does not perform or provide any of the “gender-affirming care” that is implicated in these state laws. She admitted that she “generally” does not perform diagnoses or assessments for gender dysphoria in minors and has never prescribed puberty blockers for this purpose (though she has prescribed them for other conditions). She has never been appointed as a member of any gender clinic. Since arriving at Yale School of Medicine in 2021, McNamara referred a total of two minors to its pediatric gender clinic. Neither of these patients had undergone medical “transition” as of the time of her deposition; one had not even been seen. McNamara also confessed that she had no idea how patients fared after referral to the Yale gender clinic. She did not know what percentage of patients referred to that clinic end up on a medical pathway or how many ultimately desist or detransition. And she has no firsthand knowledge of how that clinic operates—for instance, she admitted that she has never reviewed the informed-consent documents that are given to parents, so it is hard to see how she could know what kind of information is conveyed to parents as part of the informed-consent process, and whether that information is accurate or comprehensive.

This is a serious breach of trust. McNamara has repeatedly given the public, as well as judges, the impression that she is directly involved in youth gender care, but this just isn’t true at all. And if you read the deposition, which I did last month (and which I highly recommend), you’ll see that she openly admits to knowing almost nothing about this area of care. (Lydia Polgreen’s reference to this white paper in the Times wouldn’t have had the same oomph to it if she’d written that its authors included “two Yale professors, neither of whom have any clinical or research experience with youth gender medicine.”)

Not long after McNamara and her team’s Integrity Project response to Cass was complete, she filed it, under oath, as an affidavit in Boe v. Marshall. Keep that in mind as you read what follows.

So that’s the cofounder of The Integrity Project — integrity is right there in the name — which “seeks to build bridges so that sound science is accessible to litigators, regulators, legislators, and journalists.”

A List Of Objectively False Claims Made By Meredithe McNamara And Her Colleagues About The Cass Review

Early on, McNamara and her team argue that the Cass Review is broadly in agreement with the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society’s guidelines about youth gender transition. They note that “The [Cass] Review also cites a York SR that favorably appraises the WPATH Standards of Care 8 and the 2017 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines.” [4–5]

This is completely false. As a Cass Review spokesperson said in a July email:

The Statement regarding WPATH in the document on the Yale website is one of a number of misrepresentations of the conclusions of the Cass Review.

[In the systematic review], WPATH scored 26/100 for rigour of development, 39/100 for editorial independence and received an overall rating of 3/7. The Systematic reviewers from the University of York did not recommend its use in clinical practice.

This is one of the strangest errors in McNamara et al. What’s noteworthy is not only how wrong the team got this, but just how much detail the first of this two–part systematic review goes into explaining the severe weaknesses with the WPATH and Endocrine Society guidelines (among others).

This would have been very difficult to miss if McNamara and her colleagues actually read the source documents carefully.

***

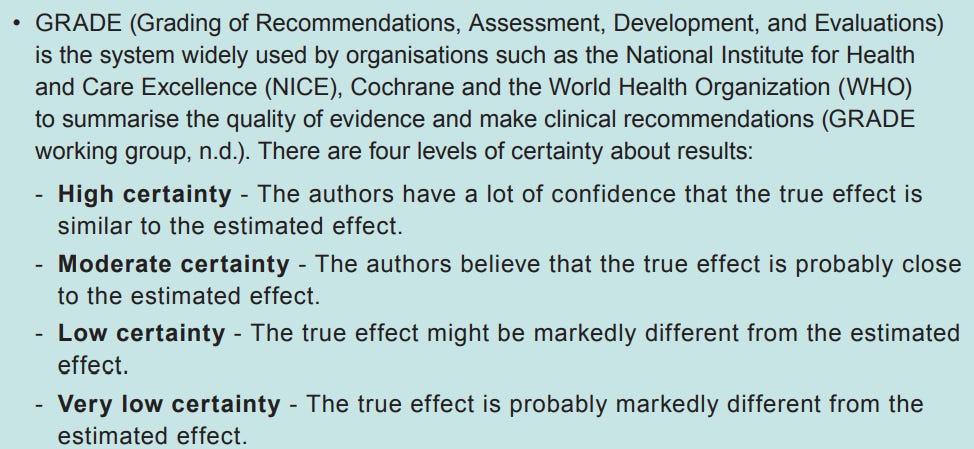

McNamara et al. argue that “The [Cass] Review casually discusses evidence quality and does not define it, contravening standard practice in scientific evaluations of medical research.” [8] On the next page they continue:

[ ] The Review also uses misleading, subjective terminology and misuses technical language regarding evidence quality. In any other field of medicine, this practice would be deemed unacceptable and harmful to patients.

The Review’s discussion of evidence quality is scientifically unsound

Under GRADE, quality designations such as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” and “very low” are used to describe evidence. There is a shared understanding of what these terms mean in medical science, which allows experts to use them in developing clinical recommendations for broad application.

The Review introduces GRADE (p 55) but never evaluates the evidence using the GRADE framework. The Review borrows GRADE terminology in repeatedly expressing a desire to see “high quality” evidence dominate the field of transgender health.

Thus, the Review falls seriously short in not describing or applying a formal method for assigning evidence quality. Thus, the Review speaks a language that may seem familiar, but its foundations are pseudoscientific and subjective. For instance, unscientific evidence quality descriptors such as “weak” and “poor” were identified 21 times and 10 times respectively. The Review’s reliance on such ambiguous terms leads readers to draw their own conclusions, which may not be scientifically informed. Such terms also undermine the rigor of the actual research, which presents much more nuanced findings than subjective descriptors convey. [9]

This gets us back into the territory of “Either the authors know this is wrong, or they don’t care.”

So: As a diagram included in the Cass Review itself points out, GRADE uses the designators “High certainty,” “Moderate certainty,” “Low certainty,” and “Very low certainty.”

McNamara and her colleagues accuse Cass and her team of “borrow[ing] GRADE terminology,” in a misleading way, “in repeatedly expressing a desire to see ‘high quality’ evidence dominate the field of transgender health.”

Except. . . “high quality” is just a normal, colloquial term to describe good evidence, certainly not restricted to GRADE settings. If you search Google Scholar for medical papers with this term, you find it used constantly, often in a colloquial manner. And while McNamara and her team claim “the Review falls seriously short in not describing or applying a formal method for assigning evidence quality,” in full context that’s false. The Cass-commissioned systematic reviews (of course) explain how they assign evidence quality ratings, and then the Cass Review points to those papers and explains how they contributed to Cass’s overall recommendations.

The Cass team again flatly denied what they were accused of here, writing to me that “On each occasion that the Review discusses quality of evidence, it refers to the various methods used to assess the evidence, and how quality was scored in the University of York systematic reviews.” I double-checked this simply by searching the Cass Review for “quality” and went through each of the 81 out of 121 mentions that precede the references section of the document. It’s of course possible I missed something, but I could not find a single example of Cass and her team referencing quality of evidence without it being clear, in context, what they meant.

To take one example, Cass and her team wrote that “A planned update of the service specification by NHS England in 2019, examined the published evidence on medical interventions in this area and found it to be weak.” This is referencing the NICE reviews of puberty blockers and hormones for youth gender dysphoria — if you’re curious exactly what “weak” means in this context, you can read them. But there’s nothing genuinely confusing here.

There is nowhere near the vagueness here that McNamara and her colleagues are suggesting, let alone any misdeed that would rise to the level of being “unacceptable and harmful to patients.”

***

Here’s another objectively false claim from McNamara and her colleagues:

Evidence certainty and quality: The Review does not describe the positive outcomes of gender-affirming medical treatments for transgender youth, including improved body satisfaction, appearance congruence, quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and mental health, as well as reduced suicidality. It is highly unusual for a document issuing clinical recommendations to not sufficiently describe the evidence on the effects of treatment. [10]

As the Cass team’s spokesperson responded to me: “The Review gives a summary of the evidence on all the above, drawn from the York systematic reviews.” This is plainly true if you read the Cass Review:

Results from five uncontrolled, observational studies suggested that, in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria, gender-affirming hormones are likely to improve symptoms of gender dysphoria, and may also improve depression, anxiety, quality of life, suicidality and psychosocial functioning. The impact of treatment on body image was unclear.

Now, the whole point is that these studies are quite weak, but it is simply false to claim that Cass and her team never describe the potential positives of these treatments. At a certain point, one has to ask whether anyone on McNamara’s team read the Cass Review carefully.

***

McNamara et al. also write that “The Review does not consider the harms of not offering gender-affirming medical care to a young person with gender dysphoria.” [10] The Cass spokesperson countered: “The Review described the impact of permanent physical characteristics which do not align with a person’s gender. This is one of the reasons that the Review recommends that puberty blockers should be available under research conditions for selected young people who may benefit.”

The Review does clearly explain the potential benefits of these medications, noting at one point that “when the Dutch gender clinic first started using puberty blockers to pause development in the early stages of puberty, it was hoped that this would lead to a better cosmetic outcome for those who went on to medical transition and would also aid diagnosis by buying more time for exploration. Since then, other proposed benefits have been suggested, including improving dysphoria and body image, and improving broader aspects of mental health and wellbeing.”

Describing the benefits of prescribing a treatment is more or less the same as describing the downsides of not treating it. And since the Cass Review does ultimately come out in favor of puberty blockers in research settings, it doesn’t really make sense to accuse the document of completely ignoring the downside of nonintervention here. To be fair, I guess one could say it’s technically true that Cass and her team merely describe the upside of prescribing rather than the downsides of not-prescribing, but on the other hand. . . come on.

***

McNamara and her team also write:

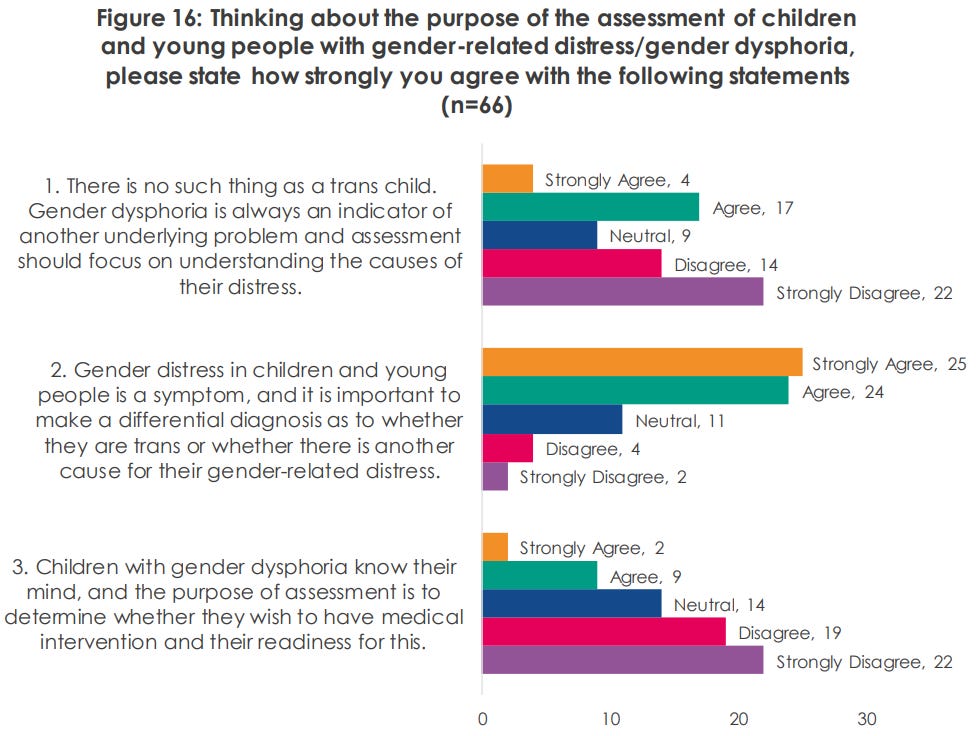

The Review solicited invalid professional viewpoints

The Review conducted a series of focus groups with healthcare workers of varying backgrounds, some of whom are not even clinicians. It is not clear what the expertise of these individuals might be in the field of transgender health. Of note, 34% stated that their understanding of “gender questioning children and young people” came from the public discourse and the media. Further, 32% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement “There is no such thing as a trans child.” Denying the existence of transgender people of any age is an invalid professional viewpoint. The involvement of those with such extreme viewpoints is a deeply concerning move for a document that issues recommendations on clinical care. A guideline that solicits opinions from those who will not acknowledge the condition for which care is sought should not be used. These individuals may express these ideological views, but their involvement in a process that led to recommendations for clinical care is a failure of the Review. [11]

This is such a severe misunderstanding (that’s the charitable interpretation) that, in my view, it constitutes a factual error: McNamara and her colleagues are claiming that a group of people who claimed “There is no such thing as a trans child” contributed to the development of the Cass Review’s clinical guidelines, but that’s just not true.

To support their claim, McNamara and her team cite this November 2021 document published by “an independent research and engagement consultancy.” This was commissioned by the Cass Review as part of its broader efforts to reform the NHS’s delivery of youth gender care, but it had nothing to do with clinical recommendations.

We need just a little background here: The Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) has been shut down and will be replaced by a more dispersed system of regional clinics. Since the new model will put more of the initial diagnostic and referring responsibility on the shoulders of primary and secondary clinicians, this survey was an attempt for the NHS to better understand the views and competencies of these clinicians — that is, ones who aren’t routinely involved in youth gender care. McNamara and her team write that “It is not clear what the expertise of these individuals might be in the field of transgender health,” but the document is clear as can be that these individuals are from outside this field! I don’t want to beat a dead horse here, but McNamara and her colleagues are all accomplished professionals, and they’re all putting their names on a document that criticizes a bunch of other named professionals (Hilary Cass and all the University of York authors). Don’t they have an obligation to at least read the documents they’re responding to?

Now, it is true that 32% of the respondents in this survey agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “There is no such thing as a trans child”:

But first, if McNamara and her team really believe that “Denying the existence of transgender people of any age is an invalid professional viewpoint,” they should be thankful to the Cass Review for revealing that, in this sample at least, a significant minority of NHS clinicians hold the view that youth gender dysphoria never indicates a permanent trans identity. And second, McNamara and her team are wrong to accuse the respondents of “not acknowledg[ing] the condition for which care is sought,” since none of the options entailed denying the existence and reality of gender dysphoria, which is the condition in question.

I wasn’t able to get an on the record quote from the Cass team here, but the spokesperson did confirm that the survey was a separate endeavor from the clinical recommendations. It is factually inaccurate to draw any connection between these focus groups and the clinical recommendations given that the former had such an explicitly different goal.

***

This next one is slightly complicated because it is true both that McNamara and her colleagues make an objectively false claim about the Cass Review, but also that Cass and her team erred.

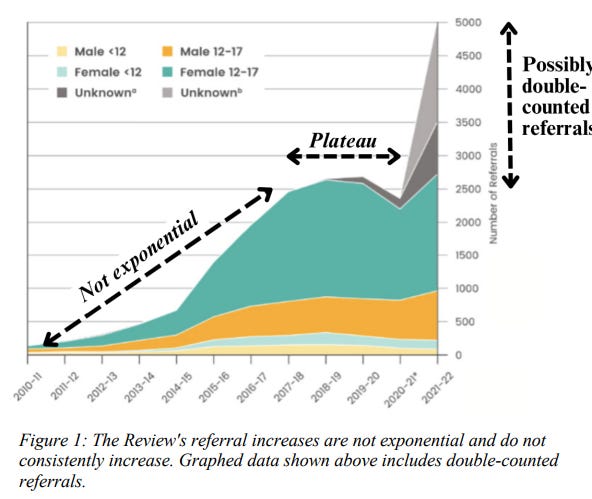

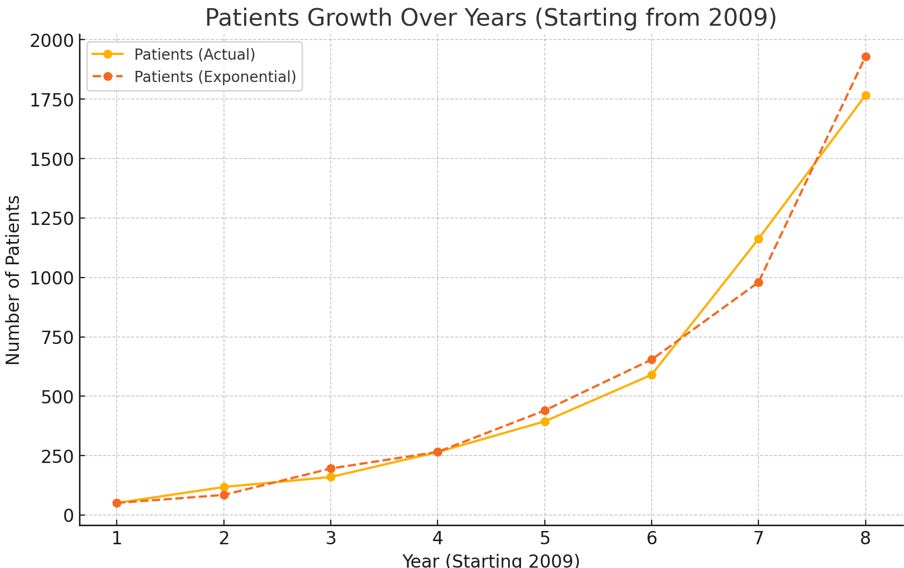

The objectively false claim: McNamara and her colleagues write that “The Review’s interpretation of this data is that it shows an ‘exponential’ increase from 2010–2022, particularly for those assigned female sex at birth.” [17]

They include this graphic from the Cass Review, with their additions in bold black letters:

This isn’t an exponential rise, they write, and Cass and her team’s use of this word constitutes “a serious error that fuels concern that the Review is too often more interested in subjective polemics than in scientific accuracy.”

The problem is, nowhere does the Cass Review argue that there was an exponential rise in referrals to GIDS from 2010 to 2022. When the document does mention an exponential rise, it’s referring to a shorter period. “The numbers of children and young people presenting to the UK NHS Gender Identity Service (GIDS) has been increasing year on year since 2009, with an exponential rise in 2014,” the authors write at one point. They subsequently describe “the exponential change in referrals over a particularly short five-year timeframe.” Elsewhere they write that “From 2014 referral rates to GIDS began to increase at an exponential rate, with the majority of referrals being birth-registered females presenting in early teenage years.” They are not saying there was an exponential rise from 2010 to 2022.

Anyway, an “exponential rise” just refers to a data series in which if you take each item and divide it by its predecessor, that ratio remains constant. The classic exponential series of 2^x starts with 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64. Since 4/2 is 2, and 32/16 is 2, and any other number in this series divided by its predecessor is 2, this is an exponential pattern.

This Substacker, Peter Sim, thinks that there was, in fact, an exponential rise in GIDS referrals from 2009 to 2016, with a ratio of about 1.66. Sim made a graph that showed how similar the actual referrals looked to an exponential curve. I tried to replicate that in a Google Sheet. I included the actual figures from 2009 to 2016 in one column (from Figure 2 of the Cass Review), and then, in another column, had Google Sheets calculate what the figures would be if they strictly followed an exponential pattern with that 1.66 base ratio, starting with the 2009 figure of 51 referrals.

Then I asked ChatGPT to graph the real dataset against the hypothetical one, and here you go:

Looks pretty exponential. As a further check I asked ChatGPT if the series was exponential, and my AI overlord answered “The ratios vary but generally stay within a range that suggests a pattern of exponential growth.”

In summary: The Cass Review said there was a pattern of exponential growth in referrals that started in 2014 and lasted five years. The authors messed up; there was a pattern of exponential growth in referrals that started in 2009 and lasted seven years.

Is this a “serious error that fuels concern that the Review is too often more interested in subjective polemics than in scientific accuracy”? That’s silly. Especially when you consider that, as Alex Byrne pointed out in a Twitter thread, Jack Turban and WPATH have both used “exponential” in a looser, non-mathematical sense in their own published work.

***

That’s it for Part 1. Part 2, which I hope to publish by next week at the latest (famous last words), will be significantly more in-depth — I’ll talk about the McNamara et al. team’s major misunderstandings of evidence-based medicine, their misrepresentations of the extant youth gender dysphoria knowledge base, and some further instances in which I think they leveled fair critiques against the Cass Review.